Guest Writer Adela Mu, MUP ’22

May 17, 2021

Note: This was written with a UDP and Seattle audience in mind. It represents only the partial perspective of the author, not that of any other person in UDP or UDP as a whole. There is far too much to say on this topic than any person is willing to read off of a website, so I have tried to be judicious with what to include. That means only a few things can be highlighted. I recognize that the two stories I chose lean heavily on the Asian perspective, which is where my own experience lies. Hopefully readers will be willing to click on the many links and resources listed here and to keep learning beyond the small sliver of filtered history presented here.

Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month falls in May for two reasons: the first Japanese immigrant arrived in the U.S. in May 1843, and the First Transcontinental Railroad, built largely by Chinese laborers, was completed in May 1869.

In the U.S., where racial relations often center on the Black-White binary, Asians (5.7% of the population) have often been ‘the invisible race,’ particularly in regions where they make up even smaller proportions of the population. Meanwhile, Pacific Islanders (0.2% of the population) are barely recognized in the continental U.S. American consciousness.

While data disaggregation for different ethnic groups is crucial to exposing the vast disparities between them, the two groups share common stories of forced assimilation and cultural erasure in the U.S. context, as do people of other problematically constructed ethno-racial groups and of the Indian Nations.

Although surges in physical and verbal assaults in the COVID-19 era (anti-Asian hate crimes surged 145% in 2020, even as overall hate crimes dropped by 6%) and the Atlanta spa shootings have brought slogans and hashtags such as #stopasianhate and #stopAAPIhate to national attention, the brief coverage in mainstream media barely scratches the surface of the long histories of discrimination, devaluation, and dismissal of Asians and Pacific Islanders in this country. Furthermore, the hyperfocus on physically violent incidents ignores the very real trauma caused by verbal assault and “microaggressions” (a misleading term because their cumulative effects are very much not micro), which have been part of the ethno-racial minority experience before and since the founding of this country.

Disaggregating Asians and Pacific Islanders

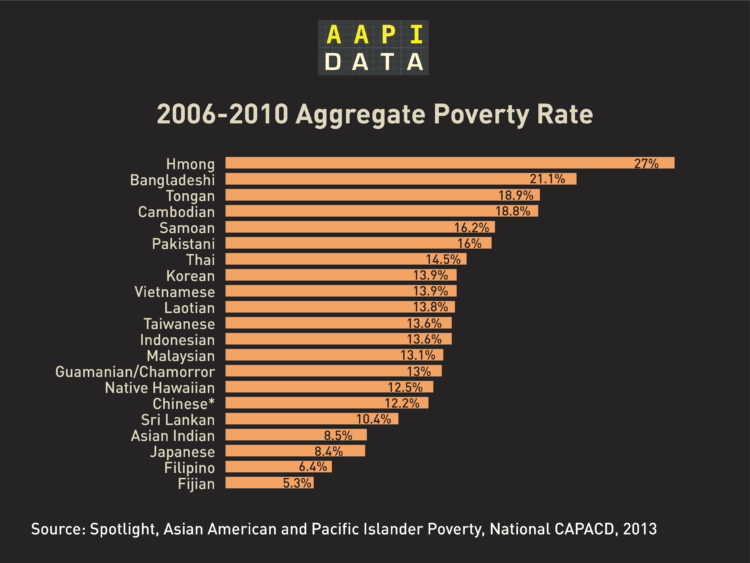

It would be remiss not to address the improper grouping of Pacific Islanders with Asians in the first place. First of all, not all Asians and all Pacific Islanders face the same issues, let alone all AAPI populations as a whole. For example, the fetishization of Asian women is most often associated with East Asians with lighter skin, while Southeast Asians (particularly Hmong, Bangladeshi, and Cambodian) and some Pacific Islanders (particularly Tongan and Samoan) tend to experience higher rates of poverty in the U.S. The Census Bureau estimates that in 2019, 10.9% of Asians lived below poverty level, compared to 17.5% of Pacific Islanders. Since the number of Pacific Islanders is small, even compared to Asians, aggregating the two groups obscures Pacific Islanders’ unique circumstances.

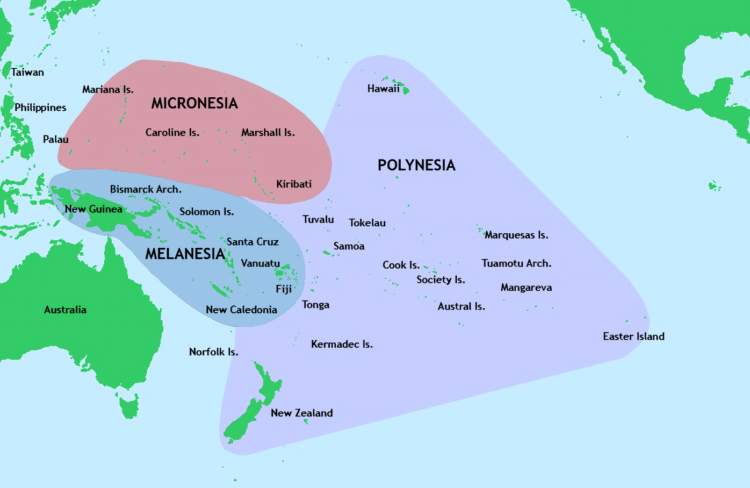

Second, Asians and Pacific Islanders have distinct histories in relation to the U.S. For example, the colonization and annexation of Hawai’i, American Samoa, the Northern Mariana Islands, and Guam (the latter three of which have severely limited representation in U.S. politics) have stripped the former nations of sovereignty. It should be recognized that the U.S. is just one colonial power out of many that have committed violence in the Pacific, including Spain, Germany, Britain, and Japan.

Lastly, unlike Asian immigrants, who are often part of growing diasporas anchored in Asian countries, many Pacific Islanders face existential threats as the islands themselves are jeopardized by climate change. Thus, in some ways, Native Hawai’ians and other Pacific Islanders share more in common with indigenous peoples on continental America than with Asian Americans. In fact, Asian American communities have sometimes been criticized for co-opting the AAPI term and overshadowing distinct needs of the Pacific Islander communities. (But that’s another essay.)

Yet, despite their differences, the ways in which people of Asian and Pacific Islander descent are construed by (White) America have common roots in xenophobic, exoticist, and colonialist tendencies, which are shared also with other racial and ethnic minorities in the country. Racism in the U.S. cannot be separated from xenophobia and notions of White/Western superiority. It is hard to believe that those who do not value the lives, knowledge, and humanity of people who live in Asia and on the Pacific Islands can somehow embrace people of Asian and Pacific Islander descent in the continental U.S. context. At the heart of these construals is the image of these peoples as sub-human, unable to self-govern, ripe for consumption and in need of rescue by the White/U.S. savior.

One example is the use of the Marshall Islands (which receives financial assistance from the U.S. under a “Compact of Free Association”) as testing and disposal grounds for 67 nuclear bombs, biological weapons (aerosolized bacteria), and irradiated soil from Nevada. More recently, the Marshall Islands and other Pacific Islands are again facing an existential threat from climate change, another manifestation of the violence waged by colonial and imperial powers. In this context, the assertion that “climate change is the biggest threat humanity has ever faced” is an obnoxiously tone-deaf claim, assertable only by those who have not experienced the many existential threats they have brought upon others. “Humanity” is thus narrowly defined by one type of people (whose composition shifts, no less) based on its own image, relegating all others to cheap labor for exploitation or inconveniences to be removed for resource extraction.

This country has a long history of dehumanizing certain populations for its convenience, including the colonization of lands and waters that indigenous peoples inhabited, the trafficking and enslavement of African peoples, and the creation of tiers of humanity whereby poverty is a crime. Yet, even against this backdrop of subjugation, there has been agency and resistance. The histories of Asians and Pacific Islanders in the U.S. are often marked by trauma, but no one people should be characterized only by its scars. As we consume stories of pain and persecution about AAPI peoples, we must also recognize their prosperity and resistance. In the rest of this acknowledgement, I will briefly highlight two examples of those who have nevertheless built and fought for their place here.

Seattle’s Chinatown-International District (CID)

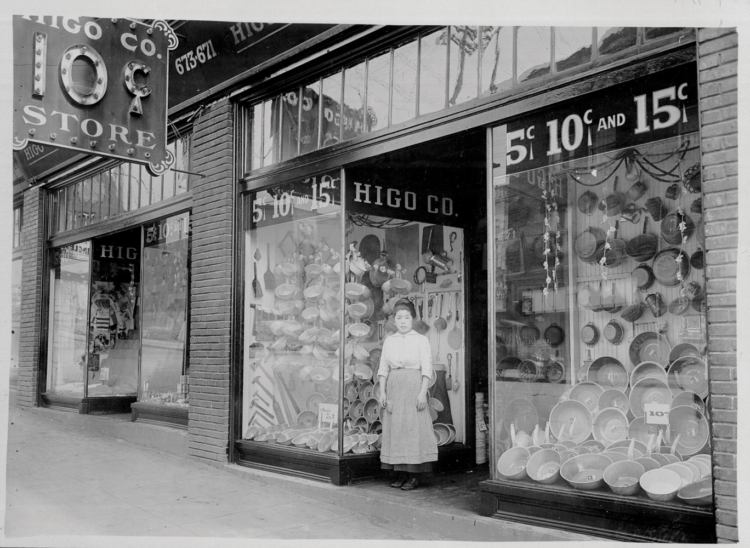

The first Asian immigrants to Seattle were Chinese laborers who worked in lumber, fishing, and railroad construction in the 1860s, and their settlement created the first Chinatown in the city. The CID in its current location was built in early 1900, after the Great Seattle Fire of 1889 destroyed the original Chinatown neighborhood along the coastline. After the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 prohibited immigration and deported hundreds of Chinese men, Japanese immigrants became the largest minority in the area because they were not subject to immigration quotas and were allowed to bring family with them. Nihonmachi (or Japantown) developed along the existing Chinatown, and a vibrant business district was born. The arrival of Filipino farm and cannery workers in the 1920s and 30s added Filipino Town (also Manilatown) to the neighborhood, and Little Saigon was established east of the CID with the arrival of Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian, and other Southeast Asian immigrants.

During WWII, as people of Japanese descent were sent to internment camps, their homes and businesses were cleared out, and the vacancies were taken over by public housing projects and parking lots. From the 1950s to 70s, construction of the I-5 highway and the Kingdome Stadium, urban renewal efforts, and strip malls further disrupted the neighborhood and increased traffic and parking demand. Although businesses in the area welcomed potential customers, they were reluctant to shift to a largely drive-by clientele that did not care about the people behind the counters. The city’s updates in building and fire codes also resulted in the closure and demolition of many older buildings.

In recent years, gentrification and speculative development makes it extremely difficult to build and preserve low-income housing in CID. As community members would say, displacement is a cumulative process: no one development destroys the community, but the neighborhood disintegrates piece-by-piece as longtime community members and businesses are pushed to leave.

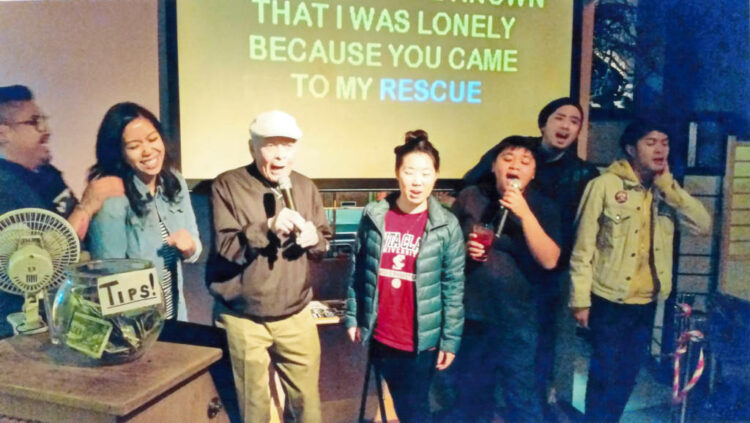

Bush Garden, one of the oldest restaurants (established 1953) in the CID and the first karaoke bar in the U.S., is a rare victory. After a battle to protect the restaurant from a development proposal for a 17-story apartment building (mostly market-rate housing), Bush Garden announced that it will be moving into a new complex. The new building, Uncle Bob’s Place, is named after Bob Santos, a revered Filipino American activist who was a regular at Bush Garden. In addition to the restaurant, Uncle Bob’s Place will feature 126 affordable housing units (below 50% AMI) and ground-floor commercial space. A virtual groundbreaking took place in February 2021.

The battle is far from over, however. Owing to its proximity to Downtown, the CID is under immense pressures of gentrification and displacement. Although the city established the International Special Review District in 1973 to preserve CID’s Asian American history, housing, and pedestrian character, the District does not cover some buildings that contribute just as much to the neighborhood’s history, including the former Bush Garden building that is slated to be demolished.

Sources:

- Gentrification in Seattle’s Chinatown-ID

- Seattle Chinatown Historic District

- Seattle Chinatown Historic District (2)

- Chinatown: History, Then and Now

- A history of change in Little Saigon

- (More) Stories of Little Saigon: Past, Present, and Future

- Vanishing Seattle Films: Chinatown-International District – Bush Garden

- International District’s Long-Running Karaoke Restaurant Will Live on in New Development

- Bush Garden to seek new location as site is developed for apartments

San Francisco’s International Hotel (I-Hotel)

In the 1960s and 70s, San Francisco was rapidly redeveloping in and around its Financial District, hoping to build a “Wall Street of the West.” Manilatown, located within the growing Financial District, was one of the city’s targets. Manilatown was a 10-block strip along the edge of Chinatown, named for the Flipino men who filled the gaps for cheap labor after the exclusion acts against Chinese (1882) and Japanese (1924) immigrants.

In the 1920s and 30s, 100,000 Filipino men came to the U.S. to work, and those in San Francisco often settled in Manilatown because of discriminatory renting practices and the verbal and physical assault they faced beyond those blocks in White neighborhoods. The International Hotel (locally called the I-Hotel) was one example of the residential hotels that offered low-cost options to the aging Filipino men, and even though the building and rooms left much to be desired, they offered a place of refuge for immigrants who were not welcome elsewhere.

When mass evictions began in the nearby neighborhoods of Western Addition (12,000 evicted) and Fillmore (4,000 evicted), largely of Black and Asian Americans, Manilatown sensed the redevelopment target on its back. Tenants fought for months against a real estate company’s proposal to build a parking lot on the site and won a three-year extension in 1969. Other similar residential hotels, however, continued to be demolished. In 1973, the I-Hotel building was sold to a Thai developer and more protests ensued.

The story reached its devastating climax on August 4, 1977, when horse-riding police broke through a barrier of protestors with batons and axed down the doors, finally dragging out tenants and protestors by their collars and arms. The I-Hotel tenants became homeless, even as the building remained vacant for two years before being demolished.

From the perspective of the long and ongoing battle for affordable housing, especially in expensive cities such as San Francisco and Seattle, the I-Hotel protest fit right in with the indignation against profit- and image-driven redevelopment. In the context of Manilatown and many more immigrant neighborhoods like it, however, the I-Hotel protest was also a fight to protect a rare refuge for working class immigrants who found new life and community in a city that otherwise rejected them. As the former President of the I-Hotel Tenants Association, Emil De Guzman, remarked, “We’ve been here for over a hundred years, but we don’t have a presence in this city. We’re overshadowed. We remain invisible.”

Almost 30 years later, Manilatown and Chinatown activists began and won the effort to build a new I-Hotel, which opened in 2005 and still contains 104 dedicated affordable housing units for senior citizens.

Sources:

Closing

Despite the disparate and often conflictual histories between the many peoples of Asia and the Pacific Islands, the AAPI populations share many experiences of discrimination, marginalization, and cultural-linguistic erasure in the U.S. History has shown that “divide and conquer” consistently proves to be a powerful and effective weapon, but we must not keep falling prey to the same old strategy. United we stand, divided we fall, and it’s harder to topple a wide base. The term “Asian American” itself was an intentional creation of the 1960s and 70s era of political consciousness among racial and ethnic minorities in this country, chosen not because Asians shared some essential identity, but to represent a coalition of solidarity. Inspired by Black Americans and their movements toward justice and recognition, Asian Americans owe many of their political victories to others who fight parallel, but not identical, battles.

Placemaking is an essential part of the human experience, and so much pain and joy is embedded in each brick, each stone, each refuge built and lost. For many marginalized peoples, the fundamental desire is to just be, to just exist and be part of a space without their presence questioned, their faces spat on, their existence negated. As placemaking professionals, urban designers and planners make decisions that directly dictate who belongs, who can occupy space, and who is allowed to imprint their existence on the built environment. History is already rife with tragedy and erasure, but the true tragedy would be if we erased that history with the violence of forgetting. If we can build places that not only tolerate, but include and celebrate those who have been razed from the country’s physical history, then perhaps we will be one step closer from an unjust past to a more just future.